Yesterday saw the launch of our report ‘Treating causes not symptoms: Basic Income as a public health measure’. The report presents the highlights of a recently-ended research project funded by the National Institute for Health and Social Care Research. This has been an interdisciplinary endeavour, involving policy and political science folk, health economists, behavioural scientists, community organizations, and two think tanks.

The public has Manichean intuitions about health. On the one hand, people feel very strongly that an affluent society should compensate and protect its members against the spectre of ill health. This is particularly true in the UK with its strong tradition of socialized care. They will support spending large amounts of money to make good health inequalities. But when you suggest that the best way for society to make good health inequalities is by removing the poverty that lies upstream of them, people often baulk. You can’t do that, surely?

I think there are a few reasons for this reaction. One is that different lay models of causation govern the two domains. Ill health seems to be all about luck, the kind of luck society should insure us against. No one sets out to get ill. Poverty seems, perhaps, to be more about character, effort and intentional action, and hence is a domain where people generally feel that individuals should fend for themselves. If there were financial handouts, some people (it is feared) would set out to live off them; but no-one suggests that because the hospitals are free, people set out to become ill and live in them. In reality, the differences between the domains of health and wealth are not so clear: health outcomes reflect character and choices as well as luck and circumstances; and financial outcomes involve a lot of luck and structural barriers as well as effort. So, some difference in kind between the two domains is not a sufficient reason for limiting policy interventions to just one of them.

Another reason for resistance is that people assume that the cost of reducing poverty is so enormous that trying to intervene at that level is simply unfeasible. Clearing up the mess we might just be able to afford; but the price tag of avoiding the mess in the first place is astronomical. It’s not clear that this is right. If reducing poverty is expensive, not reducing it is really expensive too. Already, around 45% of UK government expenditure is on the National Health Service. That direct cost is so high because the population is so sick. As well as the illnesses that need treating, there is all the work that people cannot do due to ill health. A quarter of working-age adults in the UK have a long-standing illness or condition that affects their productivity. Many of these involve stress, depression and anxiety, conditions where the income gradient is particularly steep.

These considerations raise at least the theoretical possibility that if we reduced poverty directly – via cash transfers – there might not have to be a net increase in government spending. Yes, there would be an outlay. But on the other hand, health would improve; healthcare expenditures would go down; the cost of cleaning up other social pathologies like crimes of desperation would be reduced; people would be more productive; and hence tax takes would increase. And, as I have long argued, there would be a double dividend. As we reduced people’s exposure to the sources of ill health that they cannot control, they would spontaneously take more interest in looking after themselves in the domains they can control, because it would be more worth their whiles to do so. Eliminating poverty is an investment that might not just be affordable, but even profitable.

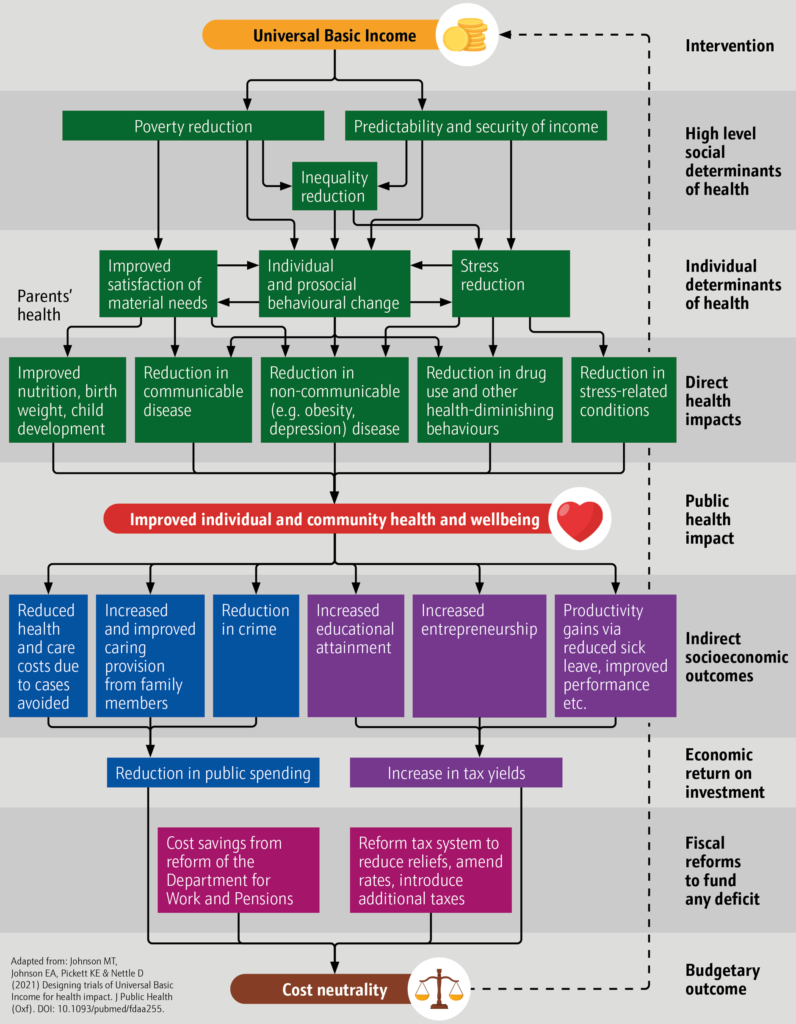

It’s all summed up in figure 1 (yes, you can tell I am becoming a real social scientist, I have a barely-legible diagram with lots of boxes and many arrows between them). Reducing poverty hits the social determinants of health. It’s cleaning the stream near its source. Downstream, the individual determinants of health are improved; downstream of that, there are better health outcomes; and downstream of that, all the social and economic benefits. Depending on the costs, and on the strengths of the various connections, there might be cash transfer systems that would pay for themselves.

This is the possibility that the NIHR funded us to model. That they would do so gives you some indication of the health crisis times we are living in. The NIHR is a hard-headed funder whose mission is to get the best possible cost-benefit ratio for the UK healthcare pound. Even they – hardly utopian or politically radical by mission – can see that paying for ever-better sticking plasters might not be the only course worthy of serious consideration.

To chunk through the net consequences of a cash transfer scheme as per figure 1 involves a lot of estimates: estimating the effect of the scheme on the distribution of household incomes; estimating the effects of household income on physical and mental health; and estimating the effects of better physical and mental health on economic behaviour and tax revenues. Each of these steps is full of uncertainty of course. It’s been a privilege to work alongside my health economics colleagues who have made serious attempts to estimate these things, as best they can, based on data. There were some things we were not able to estimate and made no attempt to include in the models. For example, I suspect that making people’s lives more predictable, as you would with a basic income, has a positive health value above and beyond the actual amount of income you give them. This is not factored into the calculations. Neither is the likely reduction in crime, and hence in the fear of crime. Thus, if anything, I think our estimates of potential benefits of reducing poverty are pessimistic.

I urge you to have a look at the report to see whether you find the case compelling (and there are more detailed academic papers in the pipeline). We consider three scenarios: a small basic income of £75 a week for adults under 65, with the state pension for over 65s staying as it is now; and then a medium scheme (£185) and a generous scheme (£295). I will focus here on the small scheme since the results here, for me, indicate what a no-brainer this kind of action is. Our small scheme is already fiscally neutral, with just some small changes to tax, means-tested benefits and national insurance. In other words, this scheme would cost the government nothing even without factoring in the population health benefits. Yet, it would be redistributive, with 99% of the poorest decile of households increasing their incomes by more than 5%. And because the poorest households are the ones where there is most ill health, its benefits would be dramatic despite its modest size.

Our model suggests that the small basic income scheme could prevent or postpone 124,000 cases of depressive disorder per year, and 118,000 cases of physical ill-health. The total benefit to UK population health is estimated at 130,000 QALYs per year. The QALY is a somewhat mysterious entity beloved of health economists. Very roughly, we can think of one QALY an additional year of perfect health for one person, or two extra years in a state of poorer health that they value only half as much. So, if 130,000 people, instead of dying, lived a year in perfect health, then 130,000 QALYs would be gained. That’s a lot. The department of health values a QALY at £30,000 for cost-benefit purposes. That is, if you want to be hard-headed, then it’s worth paying up to £30,000 to achieve an extra QALY of population health. That means it would be worth paying £3.9 billion a year for our basic income scheme, if it were to be evaluated as purely a health policy (imagine it, for example, as a drug, or a type of physical therapy). As I have already stressed, the scheme is fiscally neutral: it costs the government no more than the current system of taxes, allowances, and benefits does. The scheme is, arguably, a healthcare intervention worth £3.9 billion, available today at zero cost using only technologies that already exist. The predicted health benefits of the medium and generous schemes were much larger still; but of course, their upfront cost is larger too.

Naturally, there are many uncertainties in an exercise such as this. We took the observed associations between income and health as causal, assuming that if you boosted income, health would follow. This is an inference, and a contentious one. The way we made it – by looking at within-individual health changes when income declined or increased – is probably about the best way currently possible. But, its validity is something reasonable people could dispute. For me it brings home the serious need for proper trials of cash transfer policies, something we have written about elsewhere. Then the causal basis of the projections could be much stronger. Even accepting the limitations though, I think the case is hard to ignore. This project has made me feel more strongly than ever that there are better societies out there, in a galaxy not at all far from our own; and that we lack only rational and imaginative leaders to guide us there.