Societies with higher levels of inequality have more crime, and lower levels of social trust. That’s quite a hard thing to explain: how could the distribution of wealth (which is a population-level thing) change decisions and attitudes made in the heads of individuals, like whether to offend? After all, most individuals don’t know what the population-level distribution of wealth is, only how much they have got, perhaps compared to a few others around them. Much of the extra crime in high-inequality societies is committed by people at the bottom end of the socioeconomic distribution, so clearly individual-level of resources might have something to do with the decision; but that is not so for trust: the low trust of high-inequality societies extends to everyone, rich and poor alike.

In a new paper, Benoit de Courson and I attempt to provide a simple general model of why inequality might produce high crime and low trust. (By the way, it’s Benoit’s first paper, so congratulations to him.) It’s a model in the rational-choice tradition: it assumes that when people offend (we are thinking about property crime here), they are not generally doing so out of psychopathology or error. They do so because they are trying their best to achieve their goals given their circumstances.

So what are their goals? In the model, we assume people want to maximise their level of resources in the very long term. But-and it’s a critical but- we assume that there is a ‘desperation threshold’: a level of resources below which it is disastrous to drop. The idea comes from classic models of foraging: there’s a level of food intake you have to achieve or, if you are a small bird, you starve to death. We are not thinking of the threshold as literal starvation. Rather, it’s the level of resources below which it becomes desperately hard to participate in your social group any more, below which you become destitute. If you get close to this zone, you need to get out, and immediately.

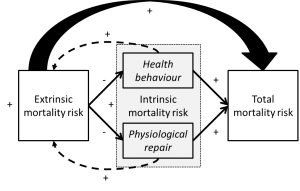

In the world of the model, there are three things you can do: work alone, which is unprofitable but safe; cooperate with others, which is profitable just as long as they do likewise; or steal, which is great if you get away with it but really bad if you get caught (we assume there are big punishments for people caught stealing). Now, which of these is the best thing to do?

The answer turns out to be: it depends. If your current resources are above the threshold, then, under the assumptions we make, it is not worth stealing. Instead, you should cooperate as long as you judge that the others around you are likely to do so too, and just work alone otherwise. If your resources are around or below the threshold, however, then, under our assumptions, you should pretty much always steal. Even if it makes you worse off on average.

This is a pretty remarkable result: why would it be so? The important thing to appreciate is that with our threshold, we have introduced a sharp non-linearity in the fitness function, or utility function, that is assumed to be driving decisions. Once you fall down below that threshold, your prospects are really dramatically worse, and you need to get back up immediately. This makes stealing a worthwhile risk. If it happens to succeed, it’s the only action with a big enough quick win to leap you back over the threshold in one bound. If, as is likely, it fails, you are scarcely worse off in the long run: your prospects were dire anyway, and they can’t get much direr. So the riskiness of stealing – it sometimes you gives you a big positive outcome and sometimes a big negative one – becomes a thing you should seek rather than avoid.

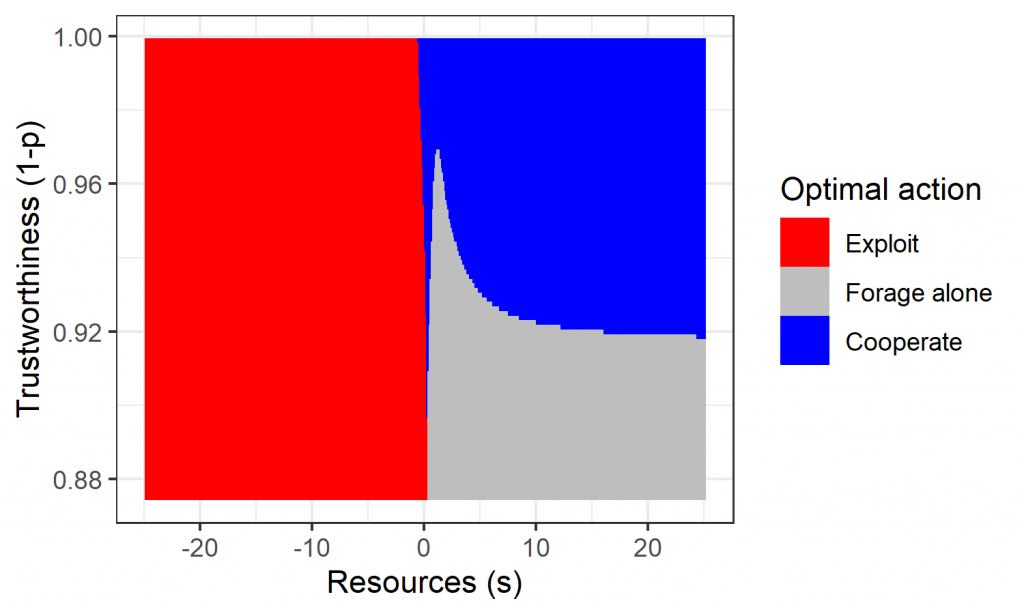

So, in summary, the optimal action to choose is as shown in figure 1. If you are doing ok, then your job is to figure out how trustworthy your fellow citizens are (how likely to cooperate): you should cooperate if they are trustworthy enough, and hunker down alone otherwise. If you are desperate, you basically have no better option than to steal.

Now then, we seem to be a long way from inequality, which is where we started. What is it about unequal populations that generates crime? Inequality is basically the spread of the distribution of resources: where inequality is high, the spread is wide. A wide spread pretty much guarantees that at least some individuals will find themselves down below the threshold at least some of the time; and figure 1 shows what we expect them to do. If the spread is narrower, then fewer people hit the threshold, and fewer people have incentives to start offending. Thus, the inequality of the resource distribution ends up determining the occurrence of stealing, even though no agent in this model ‘knows’ what that distribution looks like: each individuals only knows resources what they have, and how other individuals behaved in recent interactions.

What about trust? We assume that individuals build up trust through interacting cooperatively with others and finding that it goes ok. In low-inequality populations, where no-one is desperate and hence no-one starts offending, individuals rapidly learn that others can be trusted, everyone starts to cooperate, and all are better off over time. In high-inequality populations, the desperate are forced to steal, and the well-off are forced not to cooperate for fear of being victimized. One of the main results of Benoit’s model is that in high-inequality populations, only a few individuals actually ever steal, but still this behaviour dominates the population-level outcome, since all the would-be cooperators soon switch to distrusting solitude. It is a world of gated communities.

Another interesting feature is that making punishments more severe has almost no effect at all on the results shown in figure 1. If you are below the threshold, you should steal even if the punishment is arbitrarily large. Why? Because of the non-linearity of the utility function: if your act succeeds, your prospects are suddenly massively better, and if it fails, there is scarcely any worse off that it is possible to be. This result could be important. Criminologists and economists have worried why it is that making sentences tougher does not seem to deter offending in the way it feels intuitively like it ought. This is potentially an answer. When you have basically nothing left to lose, it really does not matter how much people take off you.

In fact, our analyses suggest some conditions under which making sentences tougher would actually be counterproductive. Mild punishments disincentivize at the margin. Severe sentences can make individuals so much worse off that there may be no feasible legitimate way for them to ever regain the happy zone above the threshold. By imposing a really big cost on them through a huge punishment, you may be committing them to a life where the only recourse is ever more desperate attempts to leapfrog themselves back to safety via illegitimate means.

So if making sentences tougher does not solve the problems of crime in high-inequality populations, according to the model, is there anything that does? Well, yes: and readers of this blog may not be surprised to hear me mention it. Redistribution. If people who are facing desperation can expect their fortunes to improve by other means, such as redistributive action, then they don’t need to employ such desperate means as stealing. They will get back up there anyway. Our model shows that a shuffling of resources so that the worst off are lifted up and the top end is brought down can dramatically reduce stealing, and hence increase trust. (In an early version of this work, we simulated the effects of a scenario we named ‘Corbyn victory’: remember then?).

The idea of a desperation threshold does not seem too implausible, but it is a key assumption of our model, on which all the results depend. Our next step is to try to build experimental worlds in which such a threshold is present – it is not a feature of typical behavioural-economic games – and see if people really do respond as predicted by the model.

De Courson, B., Nettle, D. Why do inequality and deprivation produce high crime and low trust?. Scientific Reports 11, 1937 (2021).

Many collaborators contributed to this study.

Many collaborators contributed to this study.

ew paper coming out in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences

ew paper coming out in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences

I am very excited about our imminent production of Matthew Warburton’s Hitting the Wall at Northern Stage on November 30th.

I am very excited about our imminent production of Matthew Warburton’s Hitting the Wall at Northern Stage on November 30th.