A common response to our work on Universal Basic Income as an anti-poverty policy is the following: ‘Well, that’s going to cost a lot of money. Rather than giving money to everyone, including lots of people who don’t need it, it would be better to target all that money on the poorest people, who really need it. You will have create a bigger anti-poverty effect that way’. There is a version of this argument here, for example.

Though this argument seems intuitively right, it’s actually not, oddly. UBI schemes of the kind we have advocated are in fact both universal (everyone gets them) and really well targeted at the poor. In fact, UBI schemes can be designed to have any precision and profile of social targeting that a policy-designer could imagine. In this post, I try to explain why.

The important thing to bear in mind is that the fiscal interaction between the state and the citizens is a two-way thing: there are both taxes (citizen to state) and transfers (state to citizen). When assessing how targeted a system is, you have to consider both of these: what is the net effect of the taxes and transfers on the income of each individual or household?

This means that although with a UBI, the transfer is universal, the net effect can be anything you like: you just set tax rates and thresholds appropriately. You can make it regressive, flat, progressive, targeted at the bottom 3%, targeted at the bottom 18%, or anything else you want to do.

In fact, here’s a theorem: the net effect of any non-universal benefit, for example a means-tested one, can be redesigned as a UBI with appropriate modification to the tax code. In the box below is a proof of this theorem (it’s really not complex). Here is the intuitive example. Let’s say you want just the bottom 10% of the income distribution to get £100 a week. You could make a transfer of £100 week to the bottom 10%; or you could, with equivalent financial effect, give everyone £100 a week and claw an extra £100 a week back from the top 90% by changing their tax thresholds and rates.

It follows that the right distinction to make is not between targeted transfer systems on the one hand and universal ones on the other. As we have seen, universal systems can be targeted. The right distinction is between ‘absent by default’ systems (the transfer is not made unless you actively apply for it), and ‘present by default’ systems (the transfer is made automatically to everyone). The question then becomes: why prefer a present-by-default system over an absent-by-default one? Why is it better, instead of giving £100 to 10% of the population, to give £100 to 100% of the population and then claw it back from 90% of them?

Actually, there are really good reasons. Absent-by-default schemes have a number of drawbacks. From the administrative side, you need an army of assessors and officers to examine people’s applications and try to keep track of their changing circumstances. But this is really hard: how can you tell how much need someone is in, or how sick they are? It means the state getting intrusively involved in people’s personal lives, and making judgements that are very difficult to make. From the user side, demonstrating eligibility is difficult and often humiliating. Even in terms of what they set out to achieve, absent-by-default systems fail. The point of the social safety net is to provide security and certainty. These are the things that people in adversity most need, and which help them make good decisions in life. Yet absent-by-default schemes like those that currently operate in most countries generate insecurity—rulings on eligibility can change at any time—and uncertainty—applicants don’t know if their application is going to succeed or be knocked back, or even when a decision will be made. And in an absent-by-default system, the support that comes through comes through retrospectively, after a delay in which the application has been assessed. By this time the person’s circumstances could have changed again, or they have got into an even worse predicament of homelessness or debt, which will cost even more to sort out.

The other great drawback of absent-by-default systems is that they always generate perverse incentives. If you have to demonstrate unemployment in order to continue to qualify, then you have an incentive not to take some part-time work offered to you; if you have to demonstrate poverty, you have an incentive never to build up savings; and if you have to demonstrate ill health, you have an incentive to remain sick. It is very hard to avoid these perverse incentives in an absent-by-default system.

Why do countries mostly have absent-by-default systems, when those systems have such obvious drawbacks? Sir William Beveridge was aware of their drawbacks back in the 1940s when he designed the UK’s current system. He favoured presence by default for child benefit and for pensions, and this has largely been maintained. He was against means testing for some of the reasons described above, but more means testing has crept into the UK system over the decades. He did however make more use of absence by default than a full UBI would. That’s because the economic situation seventy years ago was so different from the one we face now.

Seventy years ago, people of working age tended to have single, stable jobs that paid them the same wage over time, and this wage was generally sufficient for their families to live on. The two circumstances where they needed the social safety net were cyclical unemployment, and inability to work due to illness or accident. These circumstances were rare, exceptional, and easy to detect: it is relatively easy to see if a factory has been shut down, or someone has broken a leg in an industrial accident.

By contrast, today, many people have multiple concurrent or consecutive economic activities. The incomes from these fluctuates wildly and unpredictably, as in the gig economy or zero-hours contracts. It is often insufficient to live on: 61% of working-age adults in poverty in the UK today live in a household where at least one person works. The situations of need that Beveridge’s systems were designed to respond to were rare and exceptional. In the UK and other affluent countries today, need is frequent, can crop up anywhere, and waxes and wanes over time. An absent-by-default system cannot keep up with, or even assess, situations like this in any kind of reasonable or efficient way. The perverse incentives also loom large, as people avoid taking on more hours or activities so as not to trigger withdrawal of benefits.

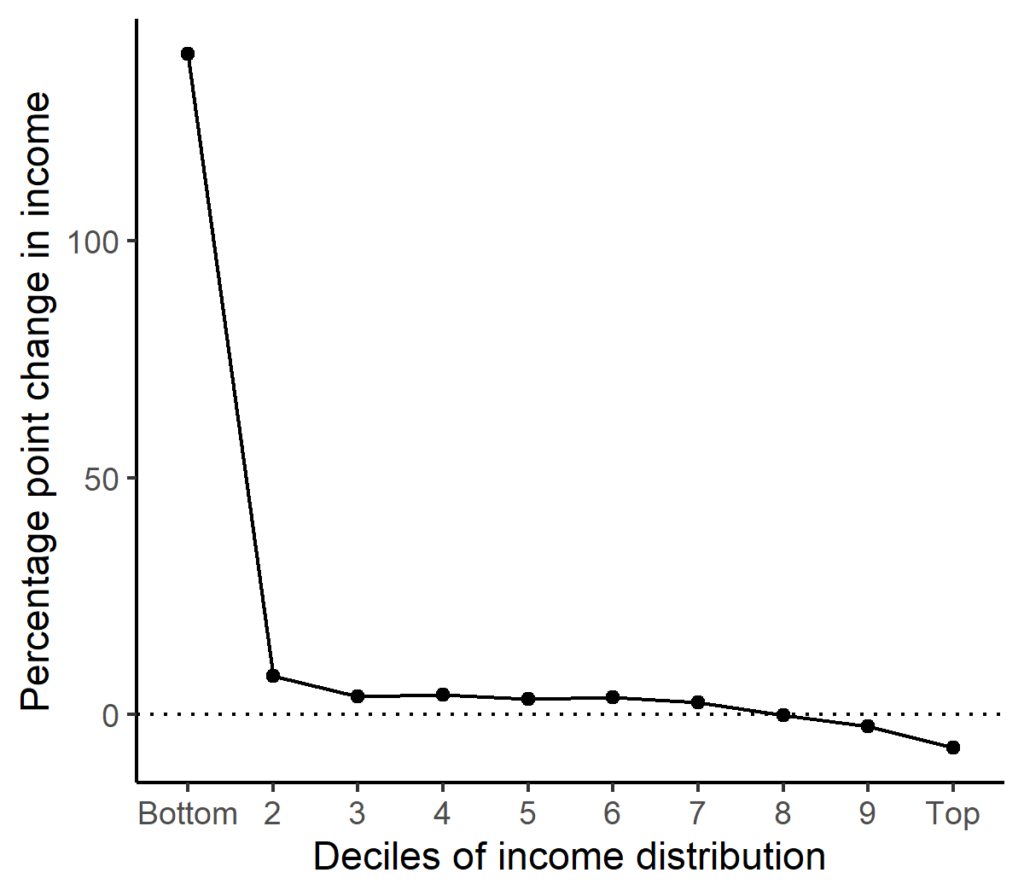

You might by now be convinced that a transfer system that is both universal and well targeted at the poor is logically possible. But I need to convince you that it is practically possible too. Figure 1 shows the net effect on people in different deciles of the income distribution of a starter Universal Basic Income scheme for the UK, as recently modelled by Reed and colleagues. The important thing about this scheme is that it is realistic and affordable. With just modest changes to the tax code, chiefly the abolition of the personal zero-tax earnings allowance, it is fiscally neutral. That means, the government does not have to spend any more money than it already does, even in the short term, in order to bring the scheme in. As you can see, although everyone would get the payments, the net benefit would be hugely greatest for the poorest 10% of the population; somewhat beneficial for everyone below the median; and only a net cost to the richest, who would be net payers-in to an even greater extent than they already are.

Figure 1. Effects of the introduction of the starter Basic Income scheme on the incomes of households in different income deciles in the UK (percentage point change on the status quo). From Reed et al. (2023).

This starter scheme would see a universal payment of £63 a week, about 70 euros. Sixty-three pounds does not seem like very much, but the scheme would still have a dramatic immediate impact on poverty. Using the conventional definition of poverty as 60% of the median income, the number of working age adults in poverty would fall by 23%, and children in poverty by 54%. The well-being impact would be larger than these figures imply, because people would have the predictability of a regular amount coming in each week that they knew would always be there. The long-run distributional consequences could be even more positive, as certainty and lack of perverse incentives allow people towards the end of the income distribution to be more active and become more productive.

Discover more from Daniel Nettle

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.