One of the big problems of the social and human sciences is the number of different kinds of explanations there are for what people do. We invoke a great range of things when we talk about why people do what they do: rational choice, conscious or unconscious motivations, meanings, norms, culture, values, social roles, social pressure, structural disadvantage…not to mention brains, hormones, genes, and evolution. Are these like the fundamental forces in physics? Or can some of them be unified with some of the others? Why are there so many? It is not even clear what the exhaustive list is; which elements on it could or should be rephrased in terms of the others; which ones we can eliminate, and which ones we really need.

It’s bad enough for those of us who do this for a living. What do the general public make of these different constructs? Which ones sound interchangeable to them and which seem importantly different? The explanation-types are sometimes grouped into some higher-order categories, such as biological vs. social. But how many of these higher groupings should there be, and what should be their membership?

In a recent paper, Karthik Panchanathan, Willem Frankenhuis and I how people understand different types of explanations; specifically, UK adults who were not professional researchers. We gave participants an explanation for why some people do something. For example, in a certain town, a large number of murders are committed every year. Researchers have ascertained that the explanation is….and then one of 12 explanations. Having done this, we then presented the participants with 11 other explanations and asked them: how similar is this new explanation for the behaviour to the one you already have? Thus, in an exploratory way, we were mapping out people’s representations of the extent to which an explanation is the same as or different from another.

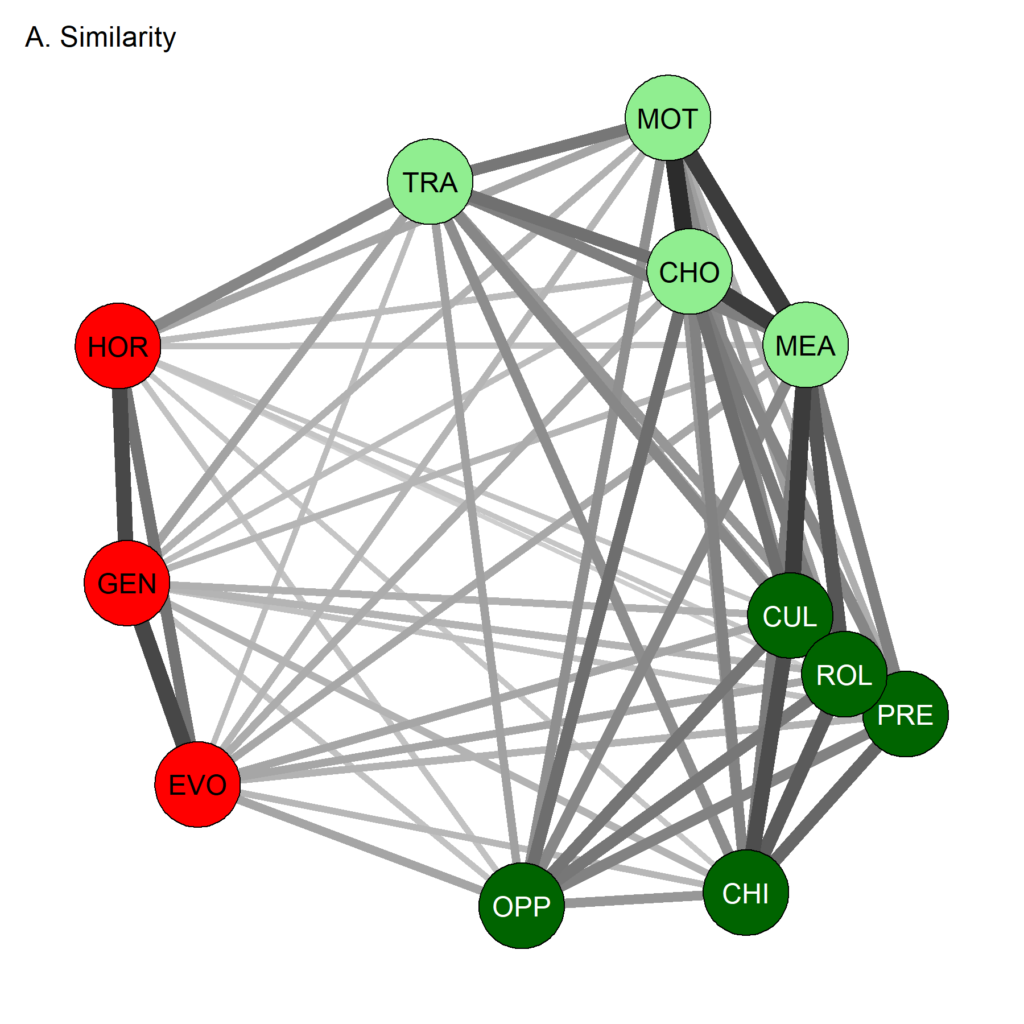

The basic result is shown in figure 1. The closer two explanations are to one another on the figure, the more similar they were seen as being. We used a technique called cluster analysis to ask how many discrete groupings it is statistically optimal to divide the graph into. The answer was three (though it depends a bit on the parameter values used). There was one grouping (hormones, genes and evolution) that definitely stood apart from all the rest. These are obviously exemplars of what people have in mind when they speak of ‘biological explanations’. The remainder of the explanations was more of a lump, but when it did divide, it fell into one group that was more about things originating in the individual actor’s head (choice, motivation, meaning, psychological traits); and another that was more to do with the expectations, pressures, and obligations that come from the way the wider social group is structured (culture, social roles, social pressure, opportunity); in other words, forces that came into the actor from outside, from society.

What we recovered, perhaps reassuringly, was a set of distinctions that is widely used in philosophy and social science. Our participants saw some explanations as biological, based on sub-personal processes that are not generally amenable to reflection or conscious volition. These were perceived as a different kind of thing from intentional psychological explanations, based on mental processes that the person might be said to have some voluntary say in or psychological awareness of, and be responsible for. These in turn were perceived as somewhat different from social-structural explanations, which are all about how the organisation and actions of a wider network of people (society) constrains, or at least strongly incentivises, individuals to act in certain ways. In other words, we found that our participants roughly saw explanations as falling into the domains of neuroscience; economics; or sociology.

So far, so good. However, it got a bit murkier when we investigated perceptions of compatibility. Philosophers have been keen to point out that although reductionist neuroscience explanations, intentional psychological explanations, and social-structural explanations are explanations of different styles and different levels, they are in principle compatible with one another. They will be, once we have polished off the small task of knowing everything about the world, completely inter-translatable. Every behavi0ur that has an intentional explanation has, in principle, a reductionist neurobiological explanation too. When you privilege one or the other, you are taking a different stance, not making a competing claim about what kind of entity the behaviour is (it’s a perspectival decision, not an ontological commitment). In other words, when you give a neuroscience explanation of a decision, and I give an intentional psychological one, it is not like a dispute between someone who says that Karl Popper was a human, and someone who says that Karl Popper was a horse. Both our accounts can be equally valid, just looking at the behaviour through a different lens.

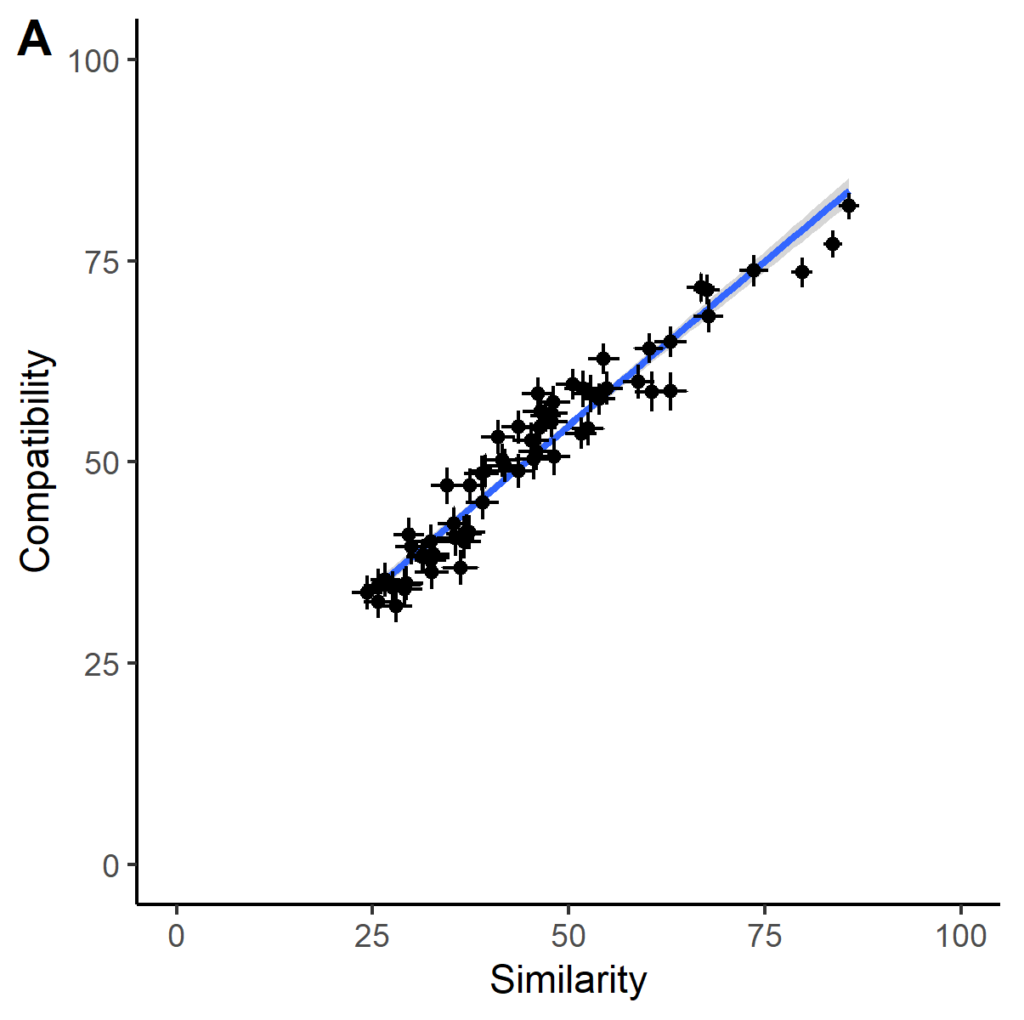

In our study, we asked a different group of people how compatible all the different types of explanation were, where, we told participants that compatible means both explanations can be true at the same time. The degree of rated compatibility was almost perfectly predicted by how similar the explanations had been rated by the people in the first sample (figure 2). In other words, explanations, for our participants, can only be true at the same time to the extent that they are similar (a norm explanation and a culture explanation for the same thing can both be true; a norm explanation and a hormonal explanation cannot). This is not really normatively right. An explanation for a fatal car accident can be given in terms of the physics (such and such masses, such and such velocities, such and such forces), and also in terms of the intentional actions (the driver’s negligence, the pedestrian’s carelessness, the mechanic’s malevolence). These explanations would be quite dissimilar, but perfectly compatible.

Our respondents’ incompatibilism, if it turns out to be typical of a wider group of people, could be problematic for science. No more so than in the case of ‘biological’ explanations for human behaviour. These being seen as the most dissimilar from intentional or social-structural explanations, they ended up being seen as rather incompatible with those others. In other words, if you say that XX’s violent outbursts are due to levels of a particular hormone, people perceive you as asserting that it must not be the case that XX is motivated by a genuine sense of moral anger; or that XX has been forced into their position by a lifetime of discrimination. Really, all three things could be simultaneously true, and could be important, but that may not be what people infer. Thus it seems worth stating – again and again, even if to you this feels obvious – that studying the neurobiological or evolutionary bases of something does not mean that the intentional level is irrelevant, or that social factors cannot explain how whatever it is came to be the case. We scientists usually see these different levels as all parts (more accurately, views) of the same puzzle; but certain audiences – many, perhaps – might see giving an explanation at a different level as more like claiming that the jigsaw puzzle is actually a chess set.

What is going on when researchers choose one kind of explanation rather than another? For example, what is at stake when we say ‘depression is a biological condition’? If what I have said about explanations being in-principle inter-translatable is true, then depression is a biological condition, but no more so than supporting Red Star FC, or having insufficient money to pay the rent, are biological. Depression is also a psychological condition, and also a social-structural one. Everything is an everything condition. In other words, ‘depression is a biological condition’ ought to assert precisely nothing at all, since explaining biologically is no more than a stance, a stance that can be taken about anything that happens to humans. The subset ‘biological’ conditions is the whole set, and perfectly overlapping with the set of psychological and social ones.

Yet, when people say ‘depression is biological’, they often seem to think they have asserted something, and indeed are taken to have done so. What is that thing?

When you choose to advance one type of explanation rather than the other, you haven’t logically ruled anything in or out, but you have created a different set of implicatures. You are making salient a particular way of potentially intervening on the world; and down-grading other possible ways of intervening. This comes from the basic pragmatics of human communication. Explanations, under the norms of human communication, should be not just true, but also relevant. In other words, when I explain an outcome to you, I should through my choice of words point you to the kind of things you could modify that would make a difference to that outcome. (Causal talk is all about identifying the things that could usefully make a difference to an outcome, not all of the things that contributed to its happening. When I explain why your house burned down on Wednesday, ‘there was oxygen in the atmosphere on Wednesday’ is a bad explanation, whereas ‘someone there was smoking on Wednesday’ is a good one. )

So, when I say ‘depression is a biological disorder’, I am taken to mean: if you want to do something about this depression thing, then it is biological interventions like drugs that you should be considering. And thus, by implication, depression is not something you can best deal with by talking, or providing social support, or increasing the minimum wage. Choosing an explanatory framing is, in effect, a way of seizing the commanding heights of a debate to make sure the search for remedies goes the way you favour. This is why Big Pharma spent so many millions over the years lobbying for psychiatric illnesses to be seen as ‘biological disorders’ and ‘diseases of the brain’ (all those findings and books about that you read in the 1980s and 1990s – they were basically Big Pharma communications, sometimes by proxy). This sets the stage for thinking more meds is the primary way of thinking about the suffering in society. We found some evidence consistent with this in our study: when we provided a ‘biological’ explanation for a behaviour, participants spontaneously inferred that it would be hard to change that behaviour, and that drug-style interventions were more likely to be the way to do it successfully.

The hostility of social scientists to ‘biological’ explanations is somewhat legendary (in fact, like a lot of legends, it’s common knowledge in some vague sense but a bit difficult to really pin down). When social scientists say ‘X [X being morality, literature, gender roles, or whatever] cannot be explained by mere biology!’, what they mean to say is not: ‘I deny that the creatures doing X are embodied biological creatures causally dependent on their nervous systems, arms, and feet to do it.’ What they are saying is something much more like: ‘I am worried that if you frame X in terms of biology, the debate will miss the important ways in which social-structural facts, or deliberate reasoning processes, have actually made the key difference to how X has come out.’ And perhaps: ‘I am particularly worried that couching X in biological terms will lead all kinds of people to assume that X must always be as it is, and could not be re-imagined in healthier ways.’ Hence, as sociologist Bernard Lahire recently put it: ‘to get too close to biology in the social sciences is to risk being accused of naturalising the current social world, of being conservative.’ In effect what social scientists are saying is not, the biology stuff is not true, but that it is not the most relevant stuff we could be talking about.

A very similar point applies to the argument between rational-choice approaches and social-structural ones. You know the old quip: economics is all about how people make choices, and sociology is all about how they have no choices to make. Essentially, critics of rational-choice economics are not saying: ‘I deny that X came about because lots of people did one thing rather than something else they could have done, and this is causally due to their agency and relative valuations of the various courses open to them’. They are saying something more like ‘I am worried that by focussing on the choice processes of the individuals involved, we will neglect the broader social configurations and institutions that are responsible for the fact that the options they had to choose between were all bad ones’; or, ‘I am particularly worried that by invoking the language of choice, the only interventions we will end up thinking about are information-giving and silly nudges, not reforming society so people have better opportunities in the first place’ (for a big debate on this topic, see here).

What to do? Fortunately, the implicature that a adopting biological framing means the appropriate level of intervention is pharmacological is a defeasible one (on defeasible and non-implicatures, see here). That is, it will be assumed to be true, unless the contrary is specified. You can, without contradiction, say: ‘depression is a biological condition, but it turns out that the best way to reduce its prevalence is to improve the social safety net, because it is brought on by poverty and isolation’. As it turns out, you not only can say this; you need to.

Discover more from Daniel Nettle

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.