Innate or acquired? Genes or culture? Nature or nurture? Biological or psychological? People are inveterately fond of trying to divide human capacities into two sorts. Commentators often seem to think that determining which capacity goes in which box is the main preoccupation of the evolutionary human sciences. (And because there is ‘evolutionary’ in the name, they think the evolutionary human sciences must be about claiming capacities for the innate/genes/nature side that the social sciences had wanted to put in acquired/culture/nurture; not really.)

In fact, innate/acquired, nature/nurture sorting is not something most of us are especially interested in. Our main hustle is that it is always both, rendering the distinction (at least as applied to mature adult capacities) somewhere between arcane and unhelpful. If it’s acquired, it’s because there are innate resources that make this possible; if it’s culture, it’s because the human genome enables this possibility, and so on. We are not interested in sorting, but in figuring out how and why things actually work. To butcher the famous exchange from The African Queen: the nature/nurture distinction, Mr. Allnut, is what we are put in this world to rise above.

But still, the widespread desire to sort capacities into two kinds persists. Why? Philosophers who have examined the problem agree that the innate/acquired dichotomy, and its companion nature/nurture, are folk or lay concepts: distinctions didn’t originally arise from formal scientific enquiry, and lack clear definitions in most people’s minds. Many but not all scientific constructs begin life as folk concepts: ‘water’ did, for example, but ‘the Higgs boson’ did not. Folk concepts can go on to give rise to useful scientific concepts. There is genuine debate in philosophy about whether a useful scientific concept of innateness can be constructed, and if so what it should be (see e.g. here and here). But regardless of how this debate is resolved, we can ask where the folk concept of innateness comes from and how people use it.

In a new paper, I argue that the folk concept of innateness is made for animals. More exactly, we have a specialized, early-developing way of thinking about animals (this way of thinking is sometimes known as intuitive biology). The folk concept of innateness comes as part of its workings. When we think about animals, we are typically concerned to rapidly learn and make available the answers to a few highly pertinent questions. First, what kind is it? Second, what’s the main generalization I need to know about that kind (will it eat me, for example, or can I eat it)? The cognition that we develop to deliver these functions is built for speed, not subtlety. It assumes that all the members of the kind are for important purposes the same (if one tiger’s dangerous, they all are), and that their key properties come straight out of some inner essence not modifiable by circumstance (doesn’t matter if you raise a tiger with lambs, it’s going to try to eat them sooner or later). When people (informally) describe a capacity as ‘innate’, part of our ‘nature’ and so on, what they mean is just this: the capacity is typical (it’s not just the one individual that has it, but the whole of their kind), and fixed (that capacity is not modifiable by circumstance). In other words, they think about that capacity the way they think about the capacities of animals.

Unfortunately, animals are not really like this. In fact, in animal species, individuals are different from one another, and far from interchangeable. This is so counter most people’s perceived experience that Darwin had to spend dozens of pages in the first part of On the Origin of Species convincing the reader that it was the case, since variation was so crucial to how his idea of natural selection worked. Moreover, animal behaviour is actually very strategic and flexible: it could well be that by raising your tiger differently, you end up with a very differently-behaving beast. But, intuitive biology is not there to make us good zoologists. It’s there to make us eat edible things and not get eaten by inedible ones.

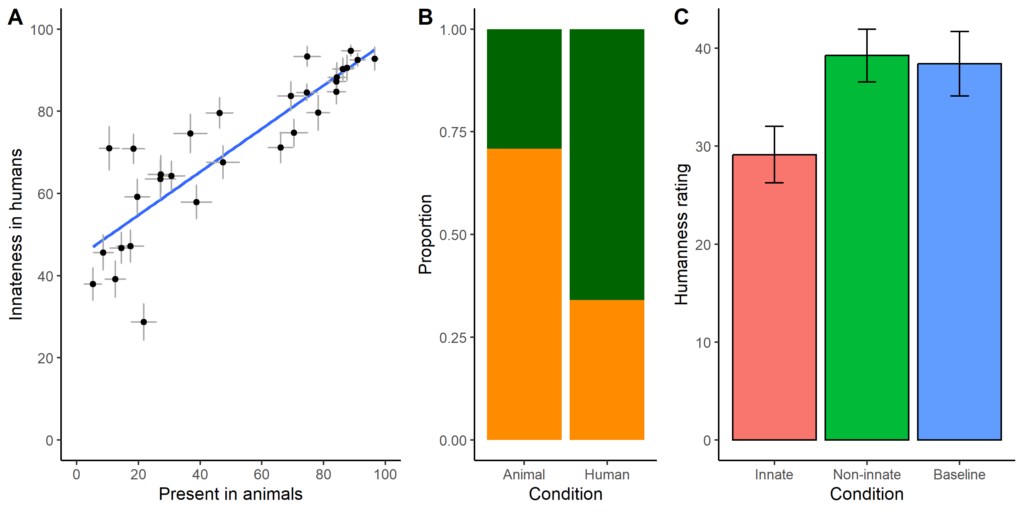

The idea that the folk concept of innateness is part of intuitive biology is not new. All my paper does is to test some obvious predictions arising from it. Working with UK-based non-academic volunteers, I found that how ‘innate’ people reckon a capacity is in humans is almost perfectly predicted by the extent to which they think other animals have it too (figure 1A). If you present people with the same capacity possessed either by an animal or a human, they think it is more likely to be innate in the animal case (with a huge effect size; figure 1B). And, even, if you tell people about an alien creature and tell them that one of its capacities is innate, they imagine that alien as less human-like than if you tell them that it had to learn its capacity, or tell them nothing at all (figure 1C). So, there is a special connection between ‘X being an animal’ and ‘X’s capacities seeming ‘innate’’.

If innateness is for animals, then we should intuitively think the capacities of humans are not innate. Indeed, several studies have shown that lay people have this prior (here and here). This is because our dominant mode for thinking about people is quite different from our dominant mode for thinking about animals. With other people, we are generally trying to manage some kind of ongoing, individual-to-individual dynamic relationship, for example of collaboration or competition. To be able to do this, you need to track individual persons, not kinds, and track what they currently know, believe, possess or are constrained by, not rely on a few context-free generalities. In other words, when we think about people (for which we use intuitive psychology), we naturally incline to thinking about what is idiosyncratic, thoughtful and contingent. Whereas for animals we pay insufficient spontaneous attention to their uniqueness and context, for humans we only pay attention to that. This sense of the idiosyncratic, the thoughtful and the contingent is what people seem to mean when they talk informally about behaviours being not innate, not in the genes, not biological and so on.

However, my participants readily assented that some capacities of humans were innate, capacities like basic sensing, moving, circadian rhythms, and homeostatic drives like hunger and thirst. These are the things about humans that you can still think about using intuitive biology: the capacities of humans qua animals. They are not the things that affect the depth of a friendship or the bitterness of a dispute; the things about people qua social agents. We tend to view other people as dual-aspect beings, having basic, embodied animal features, and complex, idiosyncratic person features; we think about these, respectively, with intuitive biology and intuitive psychology. We kind of know that these are two aspects of the same entity, but the link between the two aspects can go a bit screwy sometimes, leading to beliefs in dualism, ethereal agents, souls that leave bodies, and other shenanigans. What is often odd and jangling for people is when the language of animal bodies (genes, evolution and so on) is used in explanations for the capacities of individual people as social agents (their knowledge, decisions, and morality). That feels like it can’t be right.

This is rather a problem for researchers like me, who believe that our embodied natures and our capacities as social agents have rather a lot to do with one another (indeed, are descriptions of the same thing). If you talk about an evolved, innate or biological basis to human moral and social capacities, your audience may take you to be saying something quite different from what you intend. Specifically, you make be taken as wanting to reduce humans to beasts; to deny the critical influence of context; or to argue that human social systems must always come out the same. None of these actually follows from saying that a capacity has an evolved, innate or biological basis. It’s the folk concepts bleeding through into the scientific debate. And folk concepts, Mr. Allnut, are what we are here to rise above.