In some societies, people perceive that others can desert their existing social relationships fairly easy, in favour of alternative partners. In other societies, people feel their social relationships are more permanent fixtures, never able to be abandoned. Let’s call these high-relational-mobility societies and low-relational-mobility societies respectively. It seems intuitive that people’s trust of one another will be greater in low-relational-mobility societies than in high-relational-mobility societies. Why? Well, in those societies, you have the same interaction partners for a long time; you can know that they aren’t just going to walk away when they get a better offer; they are in it for the long term, and so their time horizon is indefinite. Seems like a recipe for trust.

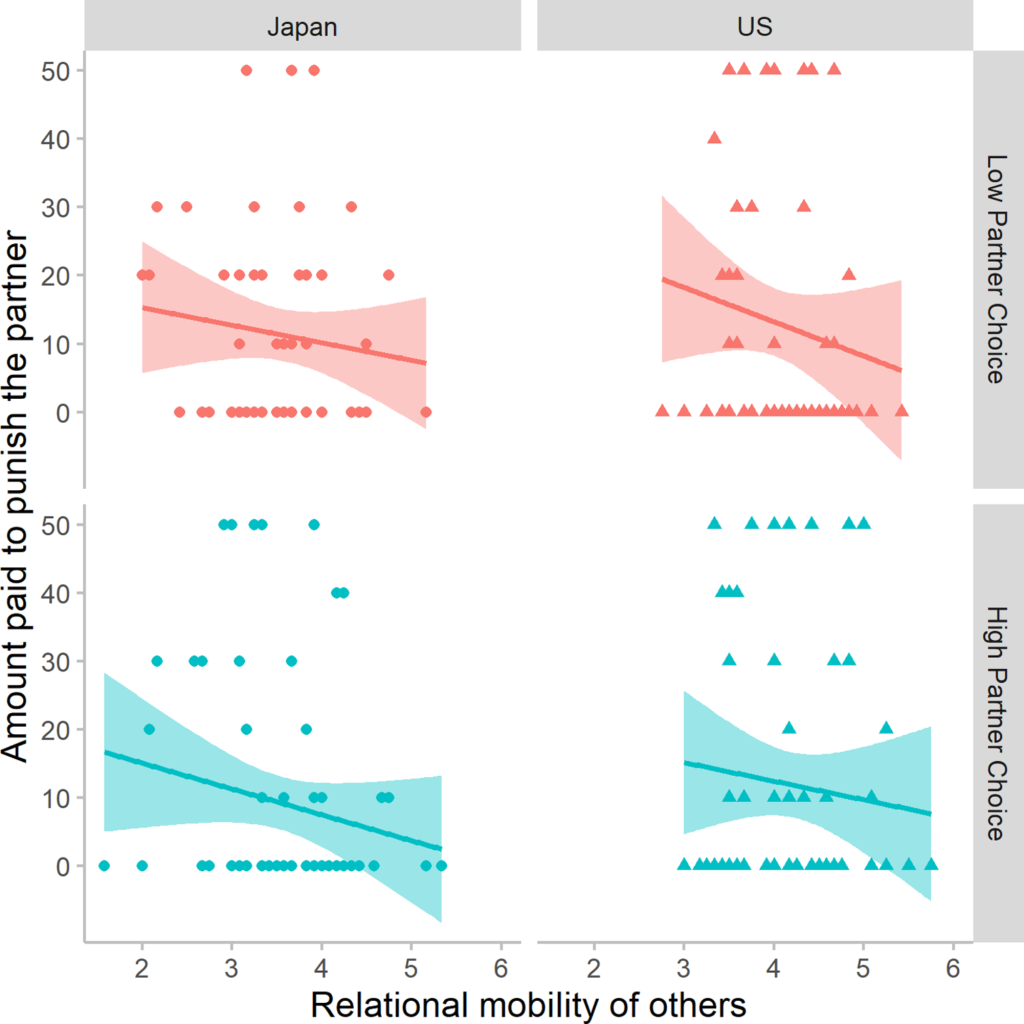

Interestingly, the empirical relationship is the other way around: where relational mobility is high, people have higher trust. Moreover, as shown in a recent paper by Sakura Arai, Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, individuals who perceive that others could walk away from them at any moment are actually more trustworthy, and less punitive. How can we explain this apparently paradoxical relationship?

The answer resembles classical arguments for the invisible hand in economics. In a market where buyers can shift vendors easily, there are many vendors, and it is easy for new vendors to enter, then I can be pretty confident that the price and service will be good. A vendor who took excessive profits, who downloaded costs onto the buyer, or was generally obnoxious would instantly and en masse be deserted. In a competitive and free market with low entry costs, I can trust that pretty much any partner I meet should treat me ok, merely from the fact of their existence.

Two allegories: high relational-mobility-societies are like Parisians believe restaurants in Paris to be: necessarily good, because there are so many restaurants in Paris and Parisian diners are so discerning that any restaurant that was not amazing and good value would have already ceased to exist. (By the way, from my own experience, I am extremely sceptical about this, not the cogency of the explanation, but the generalisation about Parisian restaurants that it is supposed to be an explanation of. I have however heard it from several independent sources.)

Second allegory: low relational mobility societies are more like the academic publishing market. We are stuck with a few massive actors (you know the ones), and our individual addictions to the status and prestige indicators they control means we, as a community, accept appalling behaviour – profit gouging, dubious editorial practices, frankly crap service to authors – rather than walking away.

In a world where the others in your social network have the option to fairly easily walk away, you have to treat those others pretty well (so that they won’t); and, they have to treat you pretty well (so that you won’t). Of course, if this meant that all relationships became transitory, ephemeral interactions, this might become pretty lonely and grim. That is not necessarily the case however: the experience of interpersonal intimacy is actually higher in high-relational-mobility societies. People value deep, durable and predictable relationships; relational mobility gives them the chance to cultivate those that suit them; and use the nuclear option to ensure a minimum acceptable threshold.

This also links to coercion and punishment. Social relationships inherently involve conflicts of interest. Thus, at some point in a social relationship, you always find yourself wanting someone to do something different than they spontaneously want to. At this point, one option is to punish them: to impose costs on them that they will find aversive. This might sometimes be effective in changing their behaviour, but it’s a horrible and humiliating way to treat someone.

If you know a person cannot walk away, punishment is a pretty effective tool, since it changes the relative payoffs of their different options to the favour of the one you want them to choose; and they can’t do much about it. But, if you know that someone subjected to the humiliation of punishment could just exit, you’d be much better off not trying to punish them – why should they put up with it? You should compromise on your demands of them instead. Thus, counter-intuitively, a good outside option on both sides can in principle make social relationships more dependable, more mutually beneficial, and freer from interpersonal domination. (Though of course, if one party has exit options and the other doesn’t, that’s an asymmetry of power, and not likely to be healthy.)

This is rich idea, foreshadowed and probed in Albert Hirschman’s classic book Exit, Voice and Loyalty. It seems to tie together lots of disparate applications. To link to one of my other areas of interest, it crops up in one of the arguments for Universal Basic Income. In a world where UBI gives every individual a minimal walk away option from every job, the labour market should get better. Humiliating and unhealthy employment practices should be lessened, as employers who treated their employees this way would go the (alleged) way of bad Parisian restaurants. This leads to the counterintuitive prediction that people would work more, or at least more happily and productively, in a world where they were paid a bit for not working.

More generally, relational mobility could play some role in explaining the expanding moral circle, the observation that as societies have become richer and more urbanised, the unacceptability of humiliation and cruelty has deepened, and been extended to successively broader sets of others. Surely, if modern economic development has done one thing, it has increased relational mobility, though unevenly (more for the rich than the poor for example, more in the metropolis than the periphery). Perhaps this is the cultural consequence.

At least, modern economic development has increased relational mobility relative to (often authoritarian) agrarian and early modern societies. Some foraging societies were probably rather different. There’s a long-standing anthropological argument that one factor maintaining egalitarianism and freedom from domination in mobile hunter-gatherers is the ability of the dominated to simply melt away and go elsewhere. Much more difficult when you are tied to a particular plot of land or irrigation resource.

To pivot to an entirely different level of analysis, narcissists, famously, have highly conflictual interpersonal relationships that nevertheless persist for years (often at great cost to the partner). Narcissists are particularly prone to trying to control their partners through punishment. Although they frequently threaten to leave (presumably as a punishment), they seldom actually do. One thing that may be going on here is that narcissists have such an inflated sense of their own worth that they struggle to believe their partners could have outside options (there is some evidence consistent with this). Thus, they like to stay, and manipulate their partner into continuing to provide benefits from them, without feeling any imperative to treat that partner well in turn.

All in all, the topic of relational mobility, at all kinds of scales, seems like an important one that requires further unifying research and theory. Is higher relational mobility an unalloyed good? Does it come with particular psychological or political costs? How does it relate to the balance of kin-based and non-kin based relationships, which has been implicated in the social evolution of trust and of economic institutions? What role does it play in ‘modernity’ more generally?

Perhaps most pressingly for me, can the power of relational mobility be harnessed from the political left? The celebration of the positive power of consumer choice has come to be strongly associated with the neoliberal right. It’s easy to see through the smokescreen here: neoliberal dismantling and privatisation of public services was rhetorically justified by the progressive power of consumer choice. In many cases it actually ended up meaning the handover of a lot of public and household money to unaccountable capitalist oligopolies (chumocracies, indeed), without much practical empowerment of the citizen. Still, people on the social democratic left have an uneasy relationship with the idea that the citizens ought to be able to choose, including choosing to opt out. Maybe, though, as in the Universal Basic Income example above, there are instances where the left can make friends with the idea.

Discover more from Daniel Nettle

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.