Like many researchers, I have been trying to up my inferential game recently. This has involved, for many projects, abandoning the frequentist Null Hypothesis Significance Testing (NHST) framework, with its familiar p-values, in favour of information-thereotic model selection, and, more recently, Bayesian inference.

Until last year, I had been holding out with NHST and p-values specifically for experimental projects, although I had mostly abandoned it for epidemiological ones. Why the difference? Well, in the first place, in an experiment or randomized control trial, but usually not in an epidemiological study, the null hypothesis of no effect is actually meaningful. It really is something you are really interested in the truth of. Most possible experimental interventions are causally inert (you know, if you wear a blue hat you don’t run faster; if you drink grenadine syrup you don’t become better at speaking Hungarian; and if you sing the Habanera from Bizet’s Carmen in your fields, as far as I am aware, your beetroots don’t grow any faster). So, although the things we try out in experiments are not usually quite as daft as this, most interventions can reasonably be expected to have zero effect. This is because most things you could possibly do – indeed, most of the actions in the universe – will be causally inert with respect to the specific outcome of interest.

In an experiment, a primary thing we want to know is does my intervention belong to the small class of things has a substantial effect on this outcome, or, more likely, does it belong to the limitless class of things that make no real difference. We actually care about whether the null hypothesis is true. And the null hypothesis really is that the effect is zero, rather than just small–precisely zero in expectation – because assignment to experimental conditions is random. Because the causally inert class is very large whereas the set of things with some causal effect is very small, it makes sense for the null hypothesis of no effect to be our starting point. Only once we can exclude it – and here comes the p-value – do other questions such as how big our effect is, what direction, whether it is bigger than those of other available interventions, what mediates it, and so on, become focal.

So, I was pretty happy with NHST uniquely for the case of simple, fully designed experiments where a null of no effect was relevant and plausible, even if this approach was not optimal elsewhere.

However, in a few recent experiment projects (e.g. here), I turned to Bayesian models with the Bayes Factor taken as the central criterion for which hypothesis (null or non-null) the data support .(For those of you not familiar with the Bayes Factor, there are many good introductions on the web). The Bayes Factor has a number of appealing features as a replacement for the p-value as a measure of evidential strength (discussed here for example). First, it is (purportedly, see below) a continuous measure of evidential strength – as the evidence for your effect gets stronger, it gets bigger and bigger. Second, it can also provide evidence for the null hypothesis of no effect. That is, a Bayes Factor analysis can in principle tell you the difference between your data being inconclusive with respect to the experimental hypothesis, and your data telling you that the null hypothesis is really supported. The p-value cannot do this: a non-significant p-value is, by itself, mute on whether the null is true, or the null is false but you don’t have enough data to be confident this is the case.

Finally, perhaps the most appealing feature of the Bayes Factor is that you can continuously monitor the strength of evidence as the data come in, without inflating your false positive rate. Thus, instead of wastefully testing to some arbitrary number of participants, you can let the data tell you when they decisively support one hypothesis or the other, or when more information is still needed.

All of these features were useful, and off I and my collaborators set. However, as I have learned the hard way, it gets more sketchy behind the facade. First, the Bayes Factor is terribly sensitive to the priors chosen for the effect of interest (even if you choose the widely used and simple Savage-Dickey Density Ratio). And often, there are multiple non-stupid choices of prior. With modest amounts of data, these choices can give you Bayes Factors not just of different magnitudes, but actually in different directions.

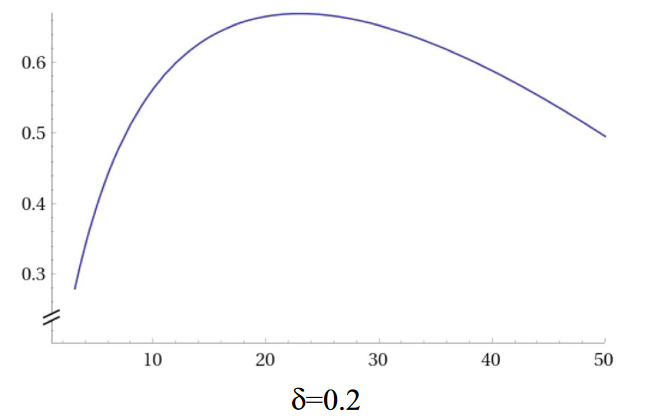

And then, as I recently discovered, it gets worse than this. For modest samples and small effects (which, realistically, is the world we live in), Bayes Factors have some ugly habits. As the amount of data increases in the presence of a true experimental effect, the Bayes Factor can swing from inconclusive to rather decidely supporting the null hypothesis, before growing out of this phase and deciding that the experimental hypothesis is in fact true. From the paper it is a bit unclear whether this wayward swing is often numerically large enough to matter in practice. But, in principle, it would be easy to stop testing in this adolescent null phase, assuming that you have no experimental effect. If substantive, this effect would undermine one of the key attractions of using the Bayes Factor in the first place.

What to do? Better statisticians than me will doubtless have views. I will however make a couple of points.

The first is that doing Bayesian inference and using Bayes Factors are very much not the same thing. Indeed, the Bayes Factor is not really an orthodox part of the Bayesian armamentarium. People who are Bayesians dans leur ames don’t discuss or use the Bayes Factor at all, They may for all I know even regard them as degenerate or decadent. They estimate parameters and characterise their uncertainty around those estimates. The sudden popularity of Bayes Factors represents experimentalists doing NHST and wanting a Bayesian equivalent of the familiar ‘test of whether my treatment did anything’. As I mentioned at the start, in the context of the designed experiment, that seems like a reasonable thing to want.

Second, there are frequentist solutions to the shortcomings of reliance on the p-value. You can (and should) correct for multiple testing, and prespecify as few tests as possible. You can couple traditional significance tests on the null with equivalence testing. Equivalence testing asks the positive question–is my effect positively equivalent to zero–not just whether it is positively different from zero. The answers to the two questions are not mutually coupled: with an inconclusive amount of data, your effect is neither positively different from zero, nor positively equivalent to it. You just don’t know very well what it is. With NHST coupled to equivalence testing, you can hunt your effect down: has it gone to ground somewhere other than zero (yes/no); and has it gone to ground at zero (yes/no); or is it still at large somewhere? Equivalence testing should get a whole lot easier now with the availability of the updated TOSTer R package by Aaron Caldwell, building on the work of Daniel Lakens.

Equivalence testing, though, does force us to confront the interesting question of what it means for the null hypothesis to be true enough. This is a bit weaker than it being truly true, but not quite the same as it being truly false, if you take my meaning. For example, if your intervention increases your outcome measure by 0.1%, the null hypothesis of zero is not literally true; you have somehow done something. But, damnit, your mastery of the causal levers does not seem very impressive, and the logical basis or practical justification for choosing that particular intervention is probably not supported. So, in equivalence testing, you have to decide (and you should do so in advance) what the range of practical equivalence to zero is in your case – i.e. what kind of an impact are you going to identify as too small to support your causal or practical claim.

So that seems to leave the one holdout advantage of the Bayes Factor approach, the fact that you can continuously monitor the strength of evidence as the data come in, and hence decide when you have enough, without causing grave problems of multiple testing. I won’t say much about this, except that there are NHST methods for peeking at data without inflating false positives. They involve correcting your p-values, and they are not unduly restrictive.

So, if your quest is still for simple tests of whether your experimental treatment did something or nothing, the Bayes Factor does have some downsides, and you still have other options.