I have seldom had much to say on the watching eyes effect. Even though it is the most cited research I have ever been involved in, it was always a side project for me, and also for Melissa Bateson, and so neither of us has been very active in the debate that goes on around it. Along with our students, we did an enjoyable series of field experiments using watching eyes to impact prosocial and antisocial behaviour. The results have all been published and speak for themselves: not much more to say (we really don’t have a file drawer). However, I have just finished reading not one but two unrelated books (this one and this one) that cite our watching eyes coffee room experiment as a specimen of the species ‘cute psychology effect that failed to survive the replication crisis’, and so I feel I do need to break cover somewhat and make some remarks.

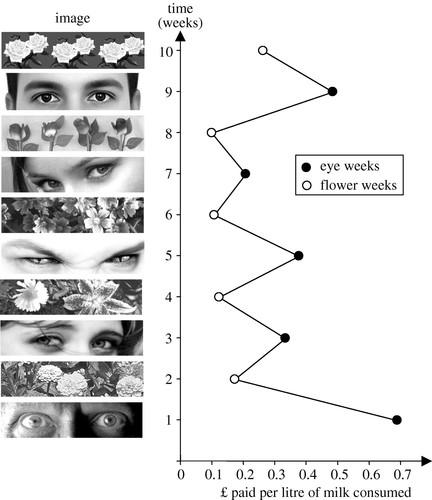

In our coffee room experiment, we found that contributions to an honesty box for paying for coffee substantially increased when we stuck photocopied images of eyes on the wall in the coffee corner, compared to when we stuck images of flowers on the wall. This makes the point that people are generally nicer, more cooperative, more ethical, when they believe they are being watched, a point that I believe, in general terms, to be true.

The account of the experiment’s afterlife in both books goes something like: this was a fun result, it made intuitive sense, but it subsequently failed to replicate, and so it belongs to the class of psychology effects that is not reliable, or at least, whose effect size is very much smaller than originally thought. It is certainly true that many psychology effects of that vintage turn out not to be reliable in just such a way; and also true that there are many null results appearing using watching eyes manipulations. I just want to point out, though, that the statement that our coffee room results have failed to replicate is not, to my knowledge, a correct one (and my knowledge might be the problem here, I have not really kept up with this stuff as well as I should).

The key point arising from our coffee room experiment was that: in (1) real-world prosocial tasks, when (2) people do not know they are taking part in an experiment, (3) few real eyes are around , and (4) the rate of spontaneous prosociality is low, then displaying images of watching eyes can increase the rate of prosocial compliance. I do not know of any attempt at a direct replication, with either a positive or a null result. We can’t do one because we don’t have a kitchen with an honesty box any more, and besides, our study population knows all about our antics by now. Someone else should do one. Indeed, many people should.

There have been some conceptual replications published, preserving all of features (1) – (4), but focusing on a different behaviour and setting than paying for one’s coffee in a coffee room. Some of these are by our students (here and here for example). Some are not: for example, see this 2016 study on charitable donations in a Japanese tavern or izakaya and the anti-dog littering campaign developed and evaluated by charity Keep Britain Tidy. All of these can be considered positive replications in that features (1)-(4) were present, a watching eyes image intervention was used, and there was a positive effect of the eye images on the behaviour. The effect sizes may have been smaller than our original study: it is hard to compare directly given the different designs, and I have not tried to do so. But, all these studies found evidence for an effect.

Given the existence of positive conceptual replications, and the lack, to my knowledge, of any null replication, why did both books describe our coffee room result as one that had not replicated? They were referring, no doubt, to the presence in the literature of several studies in which (a) participants completed an artificial prosociality task such as a Dictator Game, when (b) they knew they were taking part in an experiment, (c) they were therefore under the observation of the experimenter in all conditions, and (d) the rate of prosociality was high at baseline; and the watching eyes effect was null.

It’s perhaps not terribly surprising that watching eyes effects are often null under circumstances (a)-(d), instead of (1)-(4). When the rate of prosociality is already high, it is not easy for a subtle intervention to make it any higher. Besides, anyone who knows they are taking part in an experiment already feels, quite realistically, that their behaviour is under scrutiny, so some eye images are unlikely to do much more on top of that. That’s the whole concern about studying prosociality in the lab: baseline rates of prosociality may be atypically high, exactly because people know that the experimenter is watching. But this should not be confused with the claim that the watching eyes effect has been shown to be unreliable under the rather different circumstances (1)-(4). That might turn out to be the case too, but, to my knowledge, it has not thus far.

There are two possible sources of the book authors’ confusion with respect to the afterlife of the effects observed in our coffee room study. The first is that they are using our coffee room experiment as a metonym for the whole of the watching eyes literature. The original studies of the watching eyes effect, the ones that preceded ours (notably this one), were done under circumstances (a)-(d), and as we have seen, those effects have not reliably replicated. But it fallacious to say thereby that our rather different studies have not replicated. Something about watching eyes effects did not replicate, our study is something about watching eyes, therefore our study did not replicate. Doesn’t quite follow. By chance, we might have stumbled on a set of circumstances where watching eyes effects are real and potentially useful, even though they turn out to be more fragile and transitory in the domain – experimental economic games – where they were first documented. Testing whether this is right requires replications that have the right properties to be sure. Doing more (easy because in the lab) replications with the wrong properties does not seem to add much at this point.

Second, the book authors were probably influenced by a published meta-analysis arguing that watching eyes do not increase generosity. Whatever its merits, that meta-analysis, by design, only included studies done under circumstances (a)-(c) (and therefore for which (d) is usually true). It did not include our coffee room study, any of our conceptual replications of our coffee room study, or any of the conceptual replications of our coffee room study done by anyone else. So, it can hardly be taken as showing that the effects in our coffee room study are not replicable. That would be like my claiming that Twenty-Twenty cricket matches are short and fun, and you responding by saying that you have been to a whole series of test matches and they were long and boring, not short and fun. True, but not relevant to my claim. My claim was not that all cricket is short and fun, only that certain forms of it may be.

It’s really important, in psychology, that we attempt and publish replications, do meta-analyses, and admit when findings turn out to be false positives. But, it’s also important to understand what the implicational scope of a non-replication is. Replication study B says nothing about the replicatory potential of the effects in study A if constitutive pillars of study A’s design are completely absent from study B, even if the manipulation is similar. Also, we really ought to do more field experiments, where participants do not know they are in an experiment and are really going about their business, if the question at hand is to do with real-world behaviour and interventions thereupon.

I am quite happy to accept the truth however the dust settles on the watching eyes effect, but for real-world prosocial behaviours in field settings when no-one is really watching and participants don’t know they are taking part in an experiment, I’m not prepared to bet against it just yet.

Subscribe to this blog by entering your email in the subscribe box on the right. Regular posts on psychology, behavioural science and society.

Discover more from Daniel Nettle

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.