On March 12th 2020, in a press conference, the UK’s chief scientific advisor Patrick Vallance stated that, in times of social challenge like the current pandemic, the people’s response is an outbreak of altruism. On the other hand, we have seen plenty of examples in the current crisis of bad behaviour: people fighting over the last bag of pasta, price gouging, flouting restrictions, and so on. So there is probably the raw material to tell both a positive and a negative story of human nature under severe threat, and both might even be true.

Rebecca Saxe and I are trying to study intuitive theories of human nature. That is, not what people actually do in times of threat or pandemic, but what people believe other people will do in such times. This is important, because so much of our own behaviour is predicated on predictions about what others will do: if I think everyone else is going to panic buy, I should probably do so too; if I think they won’t, there is no need for me to do so. We have developed a method where we ask people about hypothetical societies to which various events happen, and get our participants to predict how the individuals there will behave ‘given what you know about human nature’.

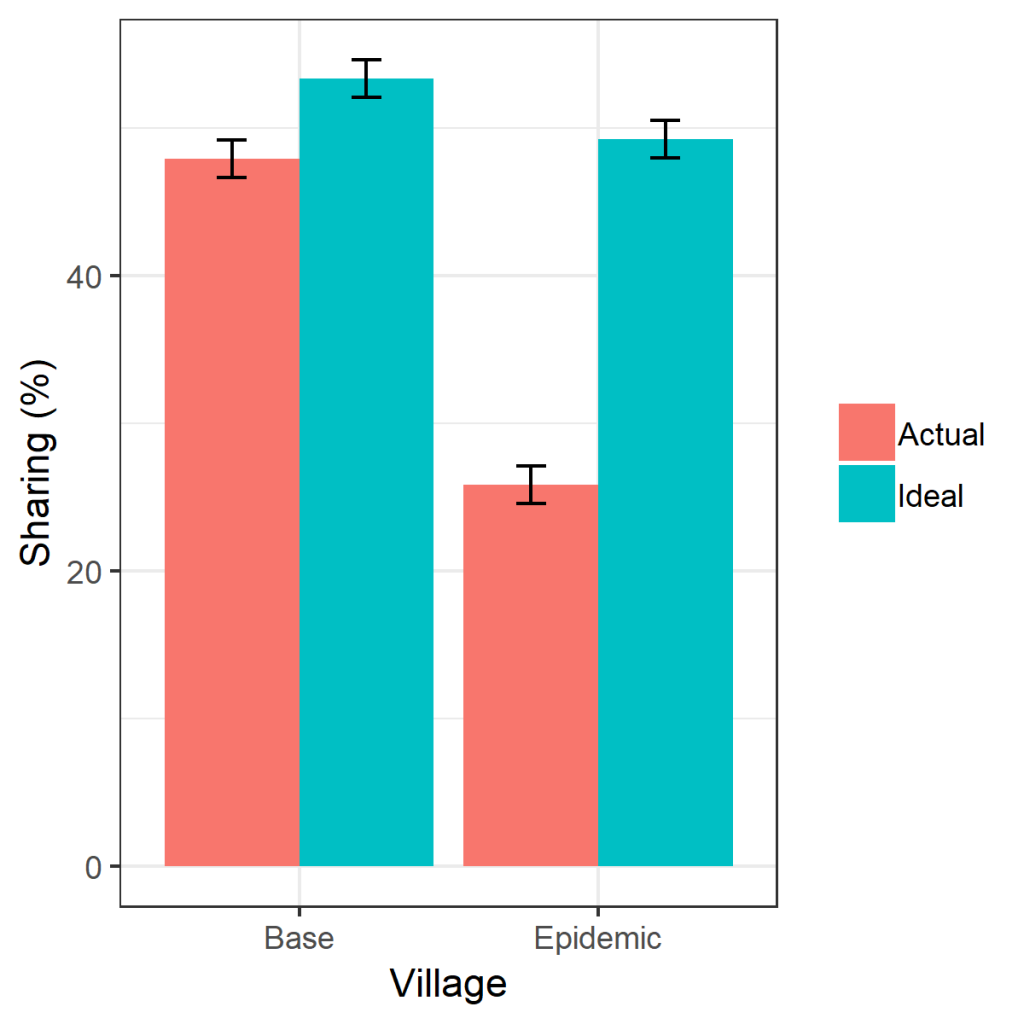

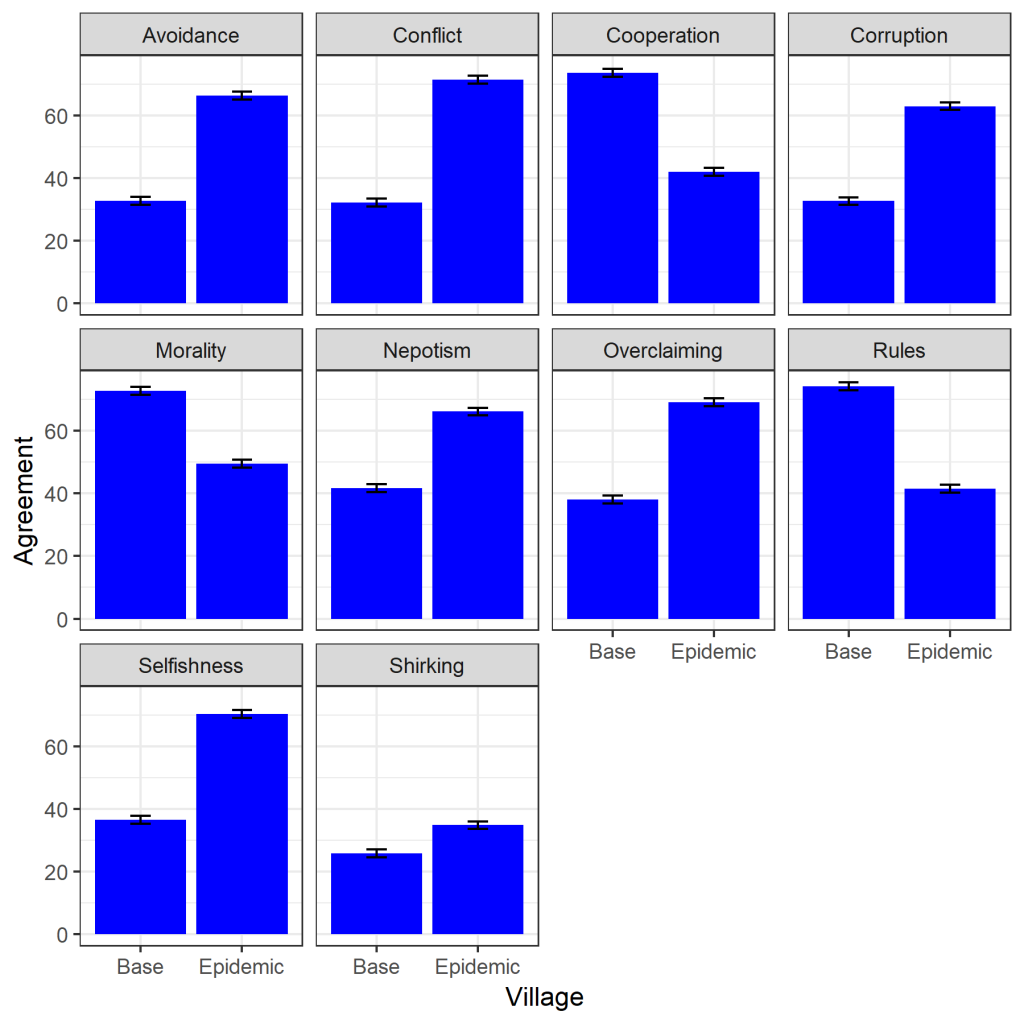

Our most recent findings (unpublished study, protocol here) suggest that (our 400 UK) participants’ intuitive theories of the response of human nature to adversity are more pessimistic than optimistic. For example, we asked what proportion of the total harvest (a) should ideally; and (b) would in practice get shared out between villagers in two agrarian villages, one living normally, and one facing an epidemic. Participants said the amount that should ideally be shared out would be nearly the same in the two cases; but the amount that actually would get shared out would be much lower in the epidemic (figure 1). Why? In the epidemic, they predicted, villagers would become more selfish and less moral; less cooperative and more nepotistic; less rule-bound and more likely to generate conflict (figure 2). One consequence of all of this predicted bad behaviour was that our participants endorsed the need for strong leadership, policing, and severe punishment in the epidemic village more than the baseline village, and felt there was less need to take the voices of the villagers into account. This is the package often referred to as right-wing authoritarianism, so our data suggest that the desire for this can be triggered by a perceived social threat and the expectation of lawlessness in the response to it.

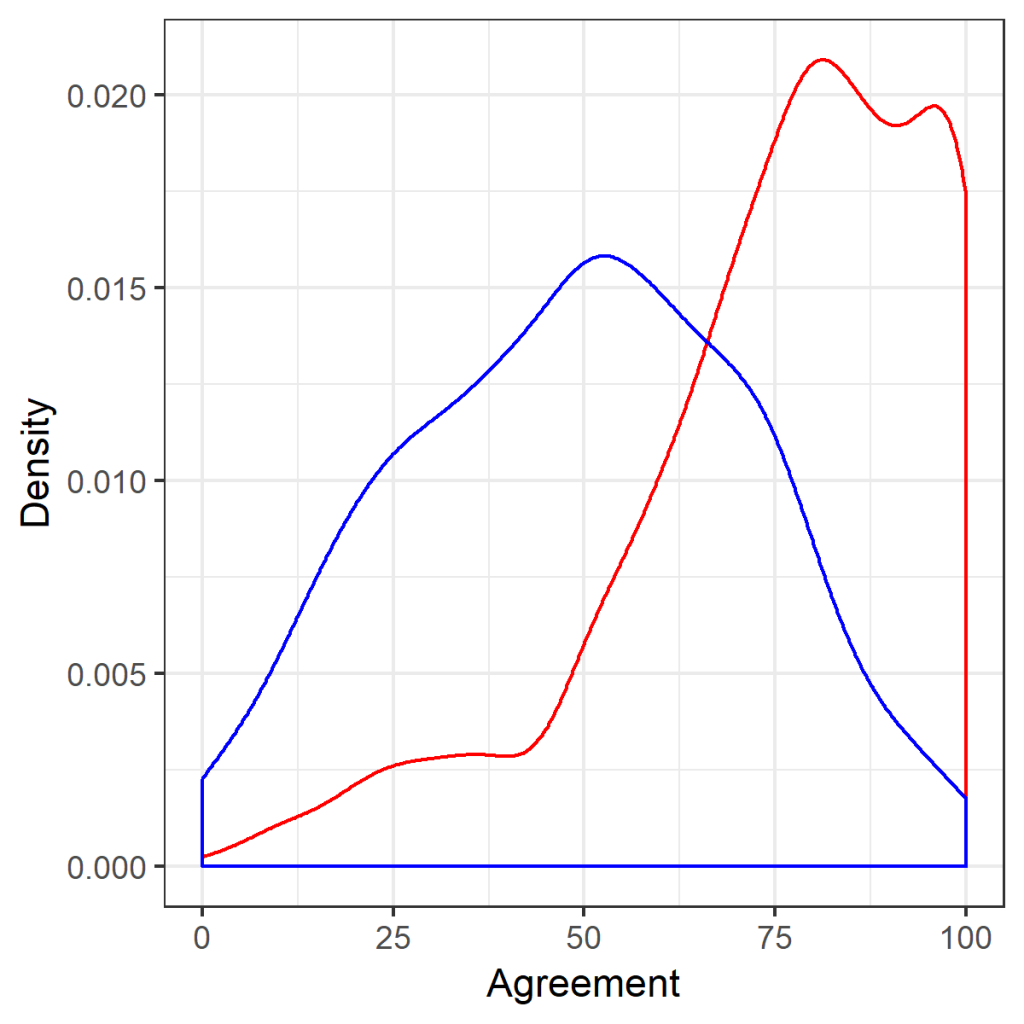

We also asked the same participants about their predictions of the response of their fellow citizens to the current real pandemic (the data were collected last Friday, March 20th). There was really strong endorsement of the proposition that other people will behave selfishly; and rather low or variable endorsement of the proposition that others will behave cooperatively (figure 3). Overall, our participants gave slightly more endorsement to the idea that the pandemic will lead to conflict and distrust than the idea that it will lead to solidarity.

So how do we square this with Vallance’s claim that there will be an outbreak of altruism, and indeed the evidence that, in under 24 hours, more than a quarter of a million people have registered as NHS volunteer responders. Well, Saxe and I are studying intuitive theories of human nature (my expectation of how you all will behave), not human nature itself (how you all actually behave). And there may be a systematic gaps between our intuitive theories of behaviour and that behaviour itself. It might even make sense that there should be such gaps. For example, what may matter for people is often avoiding the worst-case scenarios (giving all your labour when no-one else gives any; forbearing to take from the common pot when everyone else is emptying it fast), rather than predicting the most statistically likely scenarios. Thus, our intuitive theories may sometimes function to detect actually rare outcomes that are bad to not see coming when they do come (what is often known as error management). And we don’t know, when our participants say that they think that others will be selfish during the pandemic, whether they mean they think that ALL others will be selfish, or that there is a small minority who might be selfish, but this minority is important enough to attend to.

There may be very good reasons for prominent figures like Vallance to point out his expectation of an outbreak of altruism. Humans can not only behave prosocially, but also signal their intention to do so, and thus break the spiral of ‘I am only doing this because I think everyone else is going to do so’. So, if intuitive theories of human nature have a hair-trigger for detecting the selfishness of others, than it becomes important not just to actually be cooperative with one another; but to signal clearly and credibly that we are going to doing so. This is where what psychologists call ‘descriptive norms’ (beliefs about what others are doing) become so important. I will if you will. I will if you are.

One more thing of interest in our study: I have a longstanding interest in Universal Basic Income as a policy measure. We asked our 400 participants whether government assistance in this pandemic time, and normal times, should come unconditionally to every citizen, or be based on assessment of needs. We find much stronger support for unconditionality (43%) in these times than normal times (19%). This may be the moment when Universal Basic Income’s combination of extreme simplicity, ease of administration, and freedom from dependency on complex and difficult-to-track information really speak for themselves. So much that seemed politically impossible, completely off the table, as recently as January, has now actually happened, or is being quite seriously discussed. And, perhaps, once you introduce certain measures, once the pessimistic theories of human nature are defeated in their predictions of how others will respond, then people will get a taste for them.

Discover more from Daniel Nettle

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.