About five years ago I began doing meta-analyses. (If, as they say, you lose a tooth for every meta-analysis you conduct, I am now gumming my way through my food.) I was inspired by their growing role as the premier source of evidence in the health and behavioural sciences. Yes, I knew, individual studies are low-powered, depend on very specific methodological assumptions, and are often badly done; but I was impressed by the argument that if we systematically combine each of these imperfect little beams of light into one big one, we are sure to see clearly and discover The Truth. Meta-analysis was how I proposed to counter my mid-life epistemological crisis.

I was therefore depressed to read a paper by John Ionnidis, he of ‘Why most published research findings are false’ fame, on how the world is being rapidly filled up with redundant, mass produced, and often flawed meta-analyses. It is, he argues, the same old story of too much output, produced too fast, with too little thought and too many author degrees of freedom, and often publication biases and flagrant conflicts of interest to boot. Well, it’s the same old story but now at the meta-level.

Just because Ionnidis’ article said this didn’t mean I believed it of course. Perhaps it’s true in some dubious research areas where there are pharmaceutical interests, I thought, but the bits of science I care about are protected from the mass production of misleading meta-analyses because, among other reasons, the stakes are so low.

However, I have been somewhat dismayed in preparing a recent grant application on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and telomere length. The length of telomeres (DNA-protein caps on the ends of chromosomes) is a marker of ageing, and there is an argument out there (though the evidence is weaker than you might imagine, at least for adulthood) that stress accelerates telomere shortening. And having PTSD is certainly a form of stress. So: do people suffering from PTSD have shorter telomeres?

It seems that they do. There are three relevant meta-analyses all coming to the same conclusion. One of those was done by Gillian Pepper in my research group. It was very general, and only a small subset of the studies it covered were about PTSD in particular, but it did find that PTSD was associated with shorter telomere length. As I wanted some confidence about the size of the difference, I looked closely at the other two, more specialist, meta-analyses.

A meta-analysis specifically on PTSD (by Li et al) included five primary studies, and concluded that PTSD was reported with shorter telomere length by -0.19 (95% confidence interval -0.27 to -0.10). All good; but then I thought: 0.19 what? It would be normal in meta-analyses to report standardised mean differences; that is, differences between groups expressed in terms of the variability in the total sample of that particular study. But when I looked closely, this particular meta-analysis had expressed its differences absolutely, in units of the T/S ratio, the measure of relative telomere length generally used in epidemiology. The problem with this, however, is that the very first thing you ever learn about the T/S ratio is that it is not comparable across studies. A person with a T/S ratio of 1 from one particular lab might have a T/S ratio of 1.5 0r 0.75 from another lab. The T/S ratio tells you about the relative telomere lengths of several samples run in the same assay on the same PCR machine with the same control gene at the same time, but it does not mean anything that transfers across studies like ‘1 kilo’, ‘1 metre’ or ‘400 base pairs’ do.

If you don’t use standardized mean differences, integrating multiple T/S ratio studies to obtain an overall estimate of how much shorter the telomeres of PTSD sufferers are is a bit like taking one study that finds men are 6 inches taller than women, and another study that finds men are 15 centimetres taller than women, and concluding that the truth is that men are taller than women by 10.5. And the problems did not stop there: for two of the five primary studies, standard errors from the original papers had been coded as standard deviations in the meta-analysis, resulting in the effect sizes being overstated by nearly an order of magnitude. The sad thing about this state of affairs is that anyone who habitually and directly worked with T/S data would be able to tell you instantly that you can’t compare absolute T/S across studies, and that a standard deviation of 0.01 for T/S in a population study simply couldn’t be a thing. You get a larger standard deviation than that when you run the very same sample multiple times, let alone samples from different people. Division of labour in science is a beautiful thing, of course, and efficient, but having the data looked over by someone who actually does primary research using this technique would very quickly pick up nonsensical patterns.

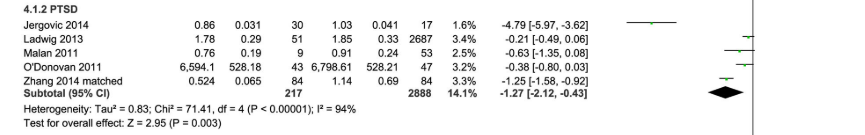

I hoped the second meta-analysis (by Darrow et al.) would save me, and in lots of ways it was indeed much better. For PTSD, it included the same five studies as the first, and sensibly used standardized mean differences rather than just differences. However, even here I found an anomaly. The authors reported that PTSD was associated with a much bigger difference in telomere length than other psychological disorders were. This naturally piqued my interest, so I looked at the forest plot for the PTSD studies. Here it is:

You can see that most of the five studies find PTSD patients have shorter telomeres than controls by maybe half a standard deviation or less. Then there is one (Jergovic 2014) that apparently reports an almost five-sigma difference in telomere length between PTSD sufferers and controls. Five sigma! That’s the level of evidence that you get when you find the Higgs boson! It would mean that PTSD suffers had telomeres something like 3500 base pairs shorter than controls. It is simply inconceivable given everything we know about telomeres–given everything, indeed, we know about whole-organism biology, epidemiology and life. There really are not any five-sigma effects.

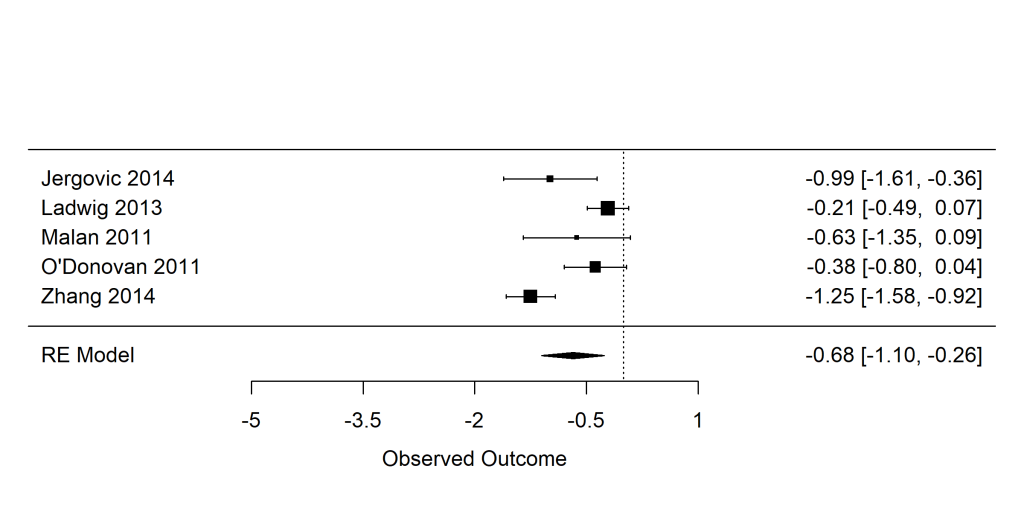

Of course, I looked it up, and the five-sigma effect is not one. This meta-analysis too had mis-recorded standard errors as standard deviations for this study. Correcting this, the forest plot should look like this:

Still an association overall, but the study by Jergovic 2014 is absolutely in line with the other four studies in finding the difference to be small. Overall, PTSD is no more strongly associated with telomere length than any other psychiatric disorder is. (To be clear, there are consistent cross-sectional associations between telomere length and psychatric disorders, though we have argued that the interpretation of these might not be what you think it is). What I find interesting is that no-one, author or peer-reviewer, looked at the forest plot and said, ‘Hmm…five sigma. That’s fairly unlikely. Maybe I need to look into it further’. It took me all of ten minutes to do this.

I don’t write this post to be smug. This was a major piece of work well done by great researchers. It probably took them many months of hard labour. I am completely sure that my own meta-analyses contain errors of this kind, probably at the same frequency, if not a higher one. I merely write to reflect the fact that, in science, the main battle is not against nature, but against our own epistemic limitations; and our main problem is not insufficient quantity of research, but insufficient quality control. We are hampered by many things: our confirmation biases, our acceptance of things we want to believe without really scrutinizing the evidence carefully enough (if the five-sigma had been in the other direction, you can be sure the researchers would have weeded it out), our desire to get the damned paper finished, the end of our funding, and the professional silos that we live in. And, as Ionnidis argued, vagaries in meta-analyses constitute a particular epistemic hazard, given the prestige and authority accorded to meta-analytic conclusions, sitting as they are supposed to do atop the hierarchy of evidence.

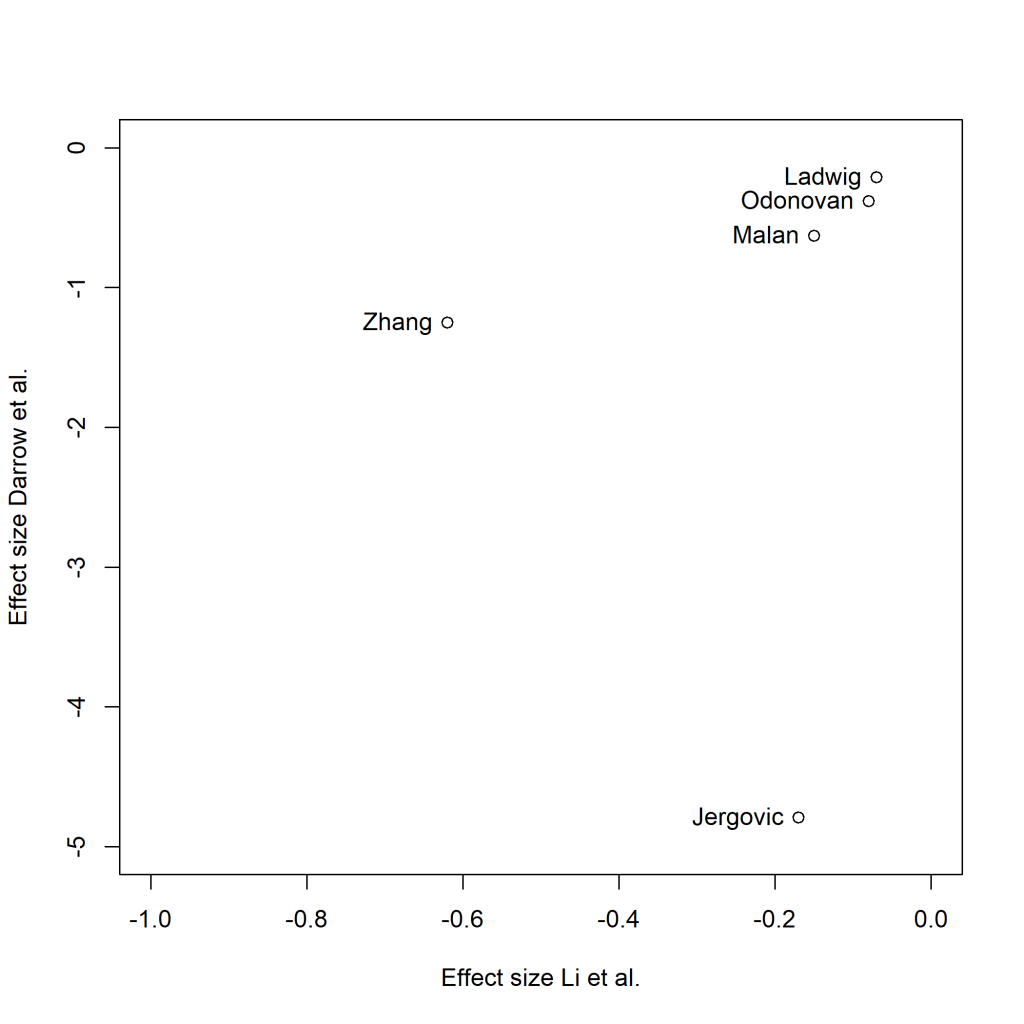

These two meta-analyses are of a relatively simple area, and cover the same 5 primary studies, and though they come reassuringly to the same qualitative conclusion, I still have no clear sense of how much shorter the telomeres of people with PTSD are than those of other people. The effect sizes found in the five primary studies as reported by Darrow et al. and by Li et al. are no better correlated than chance. So the two meta-analyses of the same five studies don’t even agree which study it was found the largest effect:

I hoped that meta-analysis would lift us above the epistemic haze, and perhaps it still will. But let’s not be too sanguine: as well as averaging out human error and researcher degrees of freedom, it is going to introduce a whole extra layer. What next? Meta-meta-analysis, of course. And after that…..?

Discover more from Daniel Nettle

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.