We’ve just published a new paper on the effects of early-life adversity in starlings. We are particularly interested in how early adversity affects the shortening of telomeres. Telomeres are the protective DNA caps on the ends of our (and their) chromosomes, whose length is often used as a marker of biological age. We have found previously that nestlings who are smaller than their brood mates lose telomeres faster in the first few weeks of life. A bad start ages you.

However, we didn’t know what it is about being at a disadvantage in the brood that accelerates telomere loss. Is it that you don’t get so much to eat? Or is it the stress of having to struggle and beg more to hold your own when those around you are bigger and stronger? Or a bit of both? We decided to test this in a hand-rearing experiment. Here, we would play the parents and thus decide what each bird experienced in its formative days.

Many collaborators contributed to this study.

Many collaborators contributed to this study.

Clare Andrews did much of the hard work

We took four siblings from each of eight wild broods. From each family, one sibling was fed all it wanted nine times a day; a second was fed nine times a day but only 70% of what the first sibling got; the third was fed all it wanted nine times a day but had to do an additional 18 minutes a day of begging; and the fourth, who had it toughest of all, received 70% of what the third sibling did, and also did the extra begging.

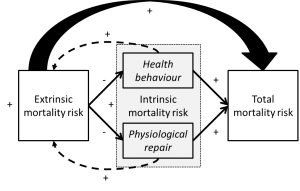

The birds all survived – in fact these adversities are well within the natural range of what a wild starling might experience. Though they all fledged into normal adult birds, we found a difference in their telomeres (in red blood cells) when they were two months old. The more adversity we had given them, the greater the magnitude of their telomere shortening over their early life. Everyone’s telomeres get shorter in this period anyway, since a lot of cell division is going on, but the birds with more adversity showed more shortening. It seems that both the amount you get to eat, and the amount you have to struggle for it, both affect the pace of your cellular ageing, and do so additively (that is, if you have both adversities, it’s worse than having either one alone). This is important, since we know in both mammals and birds that conditions experienced in early life can affect survival. Cellular ageing might point to a mechanism by which this could occur.

We also made some other curious observations. The birds showed some differences in adult inflammation according to their developmental histories, but some combinations of adversity increased adult inflammation, whilst others reduced it. Birds that had had little food, but not had to beg for it, went on to become relatively obese as juveniles (which is interesting given the links between childhood stress and obesity in humans), but birds that had had little food and had to beg for it remained lean. Thus, it looks like early-life experience matters for your biology as an adult, but it matters in complex ways, not as simple as saying ‘more early-life adversity = more adult problems’.

ew paper coming out in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences

ew paper coming out in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences